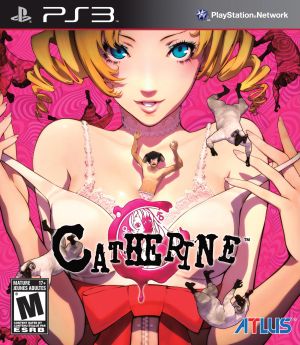

Catherine

Synopsis

Catherine is a 2011 mature horror-puzzle video game, developed and published by Atlus for PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360. The publisher describes the story as an “unconventional romantic horror.” In 2019, a remastered version of the game titled Catherine: Fully Body was released with updated gameplay, additional content, endings, and characters. Although Catherine: Full Body offers expanded content, this entry focuses on material from the version experienced by the author: the original 2011 release, currently published on Steam as Catherine Classic.

Relation to Other Horror Media

The blend of horror and puzzle elements in Catherine builds on the genre’s earlier experiments. The 7th Guest (1993) for PC, its 1995 sequel The 11th Hour, Phantasmagoria that same year, and Phantasmagoria: A Puzzle of Flesh (1996) all contained horror themes that required puzzle solving to advance the plot. Even Catherine’s blend of horror and absurdist humour could be found in 1999 with Sega’s baffling decision to translate its horror arcade shooter House of the Dead 2 into The Typing of the Dead (Gibbons 162). Although not confirmed inspirations, Catherine’s tone and game mechanics call back to the conventions these games established.

Story

The game follows Vincent Brooks and his relationship with his long-term girlfriend, Katherine. Duality is a prominent theme, with the story broken up into two halves, Vincent’s conscious and subconscious. Vincent, a video game developer in his 30s, is portrayed as a non-committal male content with living indefinitely as a bachelor. After a push to talk about marriage, Vincent is thrust into an existential crisis driven by anxiety about his future with Katherine. These events occur against the backdrop of mysterious deaths involving young men who all appear to have been unfaithful. At night he has a recurring nightmare of frantically climbing a tower of blocks, which ends in him being chased by a monster he recognizes as Katherine.

Upon waking, he sees another woman in his bed, who he learns is named Catherine. Shortly after, Vincent realizes he was seduced by her. Due to his non-confrontational nature, he fails to inform either woman of each other’s existence. The rest of the story revolves around this affair, and Vincent’s inability to confront what—or who—he truly wants. These interactions present internal moral conflicts, which manifest as monstrous forms that he attempts to escape in his nightmares.

Vincent learns that, like the men in recent news reports, death in his dreams would mean death in reality. Near the end of the game, he learns that these nightmares are caused by a God-like being named Thomas Mutton. Vincent’s only hope comes from a mysterious voice who guarantees his freedom, but only if he is able to survive for eight consecutive nights.

Autoethnographic

After hearing so many positive things about Catherine, I was eager to experience it for myself. I was initially surprised by the game’s introduction. I had never seen a video game present itself as a 1970s theatrical production, complete with a watermark in the corner for “The Golden Playhouse.” The game’s host, Trisha, drew me in with her soothing voice, while warning me of the events about to unfold. She described Vincent’s need to “overcome the massive ‘blocks’ in his life,” (Atlus) before thrusting me into the game proper. I was subsequently confronted by a man with sheep horns, clutching a pillow in nothing but his boxers.

The game began inside Vincent’s nightmare, tasking me with climbing an endless tower of cubes that quickly collapsed into a black abyss below. As time dwindled and the ornate cubes rapidly quaked and fell into nothingness, I was aggressively stirred from Trisha’s spell, frantically attempting to grasp the controls. The core gameplay mechanics involved pushing and pulling blocks in an arrangement that would create a path upwards. In theory, this is an absurdly simple concept to grasp. However, the disconnect between my primary goal of ascending higher and the techniques required to succeed were staggering. The stress of thinking logically while the threat of failure loomed constant, I became so overwhelmed that I ended up lowering the difficulty to the easiest setting. I question whether I would have been able to complete the game otherwise.

Upon waking, Vincent realized he has wet the bed. After a lunch date that made me question why he was in a relationship with Katherine in the first place, Vincent headed to the Stray Sheep. After hearing Trisha’s prologue, I acknowledged the name as a metaphor for the men who made up most of their clientele “straying from the flock”. It was here that I witnessed most of the themes of masculinity and escapism that ran through the game. The patrons appeared in Vincent’s dreams as sheep—as he did to them—and recalled nothing when they woke up. The television in the background buzzed with news coverage of young men discovered dead in their bedrooms. Meanwhile, patrons talked casually about cheating on partners, anticipated a women’s wrestling match, and played an arcade version of their nightmare realm. A game where—rather than running away from themselves—they envisioned themselves as the damsel’s saviour. Stray sheep indeed. I was able to initiate a limited number of conversations before Vincent would be forced to go home. I could have him respond to texts, chat with friends, or talk to the patrons that came and went over time.

At night, I would encounter other non-playable characters between nightmare stages. They would sometimes offer climbing tips, but otherwise simply seemed to serve as moral reflection points. Before progressing to the next stage, I was forced to enter a confession booth to answer a question that shifted Vincent’s morality towards one of the multiple endings I would eventually arrive at. Though not explicitly stated until much later, Vincent’s morality was on a scale between freedom and order. Unknown to me, my choices pushed Vincent towards a life of order and commitment to Katherine.

I came away from completing Catherine with the impression that it might be considered among the few rare truly adult games I have experienced. It did not contain the pornographic content that its marketing implied. The surface appeal in the advertising for Catherine mask the complex themes of guilt, shame, and anxiety. And by cloaking itself in that way, it embodies the themes of Vincent’s psychological horror perfectly.

Like Vincent, I was lured in by the promise of excitement and fantasy. By doing so, I became complicit in Vincent’s actions, and I could no longer claim to be an objective party. John Frow states that our direct interaction with fictional characters—like Vincent—results in recognizing them as similar to ourselves, through a process which he calls “affective engagement” (110). After all, it wasn’t just Vincent in the confession booth each night, it was me responding through him. Knowing that my answers would be compared online against my peers mirrored the same social anxiety of conformity vs autonomy that I witnessed Vincent experience. This digital avatar slowly started feeling like a real person to me as increasingly empathized with his patterns of speech, body language, and actions,. (Frow 109-111).

Duality, Morality, and Identity

It is clear from the beginning that Vincent is a flawed male figure facing an identity crisis. He is split between his selfish desire to stay comfortable in an orderly world and the fear of future resentment that would throw his life into chaos. Catherine’s horror draws from the burden of shame that Vincent feels over his indecision (Kirkland 174-175). His recurring dream of being chased by monsters up an endless collapsing tower represents the deep-rooted anxiety and guilt over his transgressions (163). This self-flagellation is also emphasized by religious imagery of catholic crucifixes, confessionals, and references to the Gods Astaroth, Dumuzid, and Ishtar. The duality of Vincent’s crisis is reflected through Katherine; a maternal, rational woman who states what she wants, and Catherine; a spiteful, impulsive, girl who will do anything to get what she wants. Vincent’s desires for order versus freedom are the pillars upon which all of the player’s choices rely.

The player’s only meaningful actions while Vincent is awake are routine interactions at the same bar, with the same people, drinking the same drinks, listening to the same music.

This stasis parallels Vincent’s inability to take decisive action, as well as his proclivity to dwell on situations through spiralling inner monologues full of guilt and turmoil. Each night Vincent repeats the loop, running for his life and climbing another endless tower. Like Sisyphus, the player can never stop climbing and is weighed down by the recognition that this cycle will repeat and no real progress will be made. Perhaps a more poignant metaphor than ever, Fisher describes a world where progress is replaced by unending toil, or “the slow cancellation of the future” (3). Michael Hancock describes this destabilizing repetition as horror that erodes the autonomy and identity of the avatar character (169). Atlus implements existential dread into the mechanics of play, where the only choices are to keep climbing or fall to your death. The metaphor of repetition is a means for the player to identify with the experience of horror in the character avatar (Frow 108). Vincent’s climb presents a haunting analog for the dread of modern life’s relentlessness. A quote penned by the French author Ernest Dimnet reads, “The happiness of most people is not ruined by great catastrophes or fatal errors, but by the repetition of slowly destructive little things” (Allgreatquotes).

Portrayals of Sexuality and Gender

Ewan Kirkland views recurring traits in male horror video game protagonists, such as Vincent’s neuroticism and cowardice, contrast the trope of “militarized masculinity” (171). Vincent’s inner conflict between the two women in his life further fuel his guilt and turmoil (167). His indecision creates a sense helplessness that follows him into his dreams, where he is controlled by outside forces (174, 178-179). His loss of control distorts his psyche into fear-based deformities that represent fatherhood, marriage, and loss of identity (Cruz 166). Visual metaphors such as the striped bars on his bedsheets and the padded wall of his headboard reinforce the domestic horror in Vincent seeing himself as a prisoner of his own life (Kirkland 171-172).

In each case, these monstrous transformations evoke horror through their grotesque anatomy exaggerated proportions (Cruz 162). Katherine’s potentially unborn child triggers Vincent’s reproductive anxiety, depicted by a gigantic screaming baby. When he suspects the child might not be his, the baby returns with a chainsaw, even more mutated and disfigured by the moral panic (165, 166).

Catherine is a manifestation of Vincent’s suppressed desires. In the gothic horror convention, Katherine is doubled into a sexually idealized doppelgänger. (Hancock 173-175). The character of Catherine is symbolic of the "sexy + gross = creepy" formula, where she appears unassumingly attractive until her monstrous form as a succubus is revealed (Stang 25, 26). Originating in 18th century French romantic literature, the succubus figure further entrenches Catherine in gothic horror themes, combining eroticism, temptation, and monstrosity (Hancock 171). The female bosses for stages two, three, five, and eight can all be seen as examples of empowered women being punished as a symbolic act of restoring patriarchal order (20). The “Immoral Beast” boss presents a mutated form of Catherine with fanged genitals exemplifies vagina dentata and castration anxiety (26).

The boss stages present female bodies and sexuality as a site for horror (30, 31). These bosses deliver lines such as, “Please...give me more!” and “You like it like this, right?” while trying to murder Vincent (Catherine Wiki). Boss stages portray female monsters using their voices as weapons to kill, incapacitate, or otherwise hinder Vincent (Stang 21-26). However, since Vincent’s problematic decisions in his relationships are not rewarded or endorsed, the game can also be argued as a critique on misogyny (175, 176).

Music

The soundtrack of Catherine further elevates the themes of duality between freedom and order. Vincent’s waking life is filled with slow and catchy jazz tunes. Conversely, his dreams sound more like a horror movie, with measured string vibrato, piano, and timpani (McKillop 4:07). Focusing on the nightmare themes, Composer Shoji Meguro blends classical and rock genres to showcase the clash between order and freedom. William Gibbons calls the choice of recognizable classical music “works you might hear in any concert hall” (3). An obvious example is the chorus from Handel’s “Hallelujah”, hitting you over the proverbial head with its overt message of joy and relief, cued at the end of each stage.

Deeper cuts can also be found, such as Georges Bizet’s "Farandole" from L'Arlésienne. This is a play about a man caught between two women and later commits suicide by jumping from a balcony. Gibbons argues the intentional mirroring of L'Arlésienne within Catherine (Gibbons 5).

The theme that plays when Vincent falls to his death during gameplay is Pablo de Sarasate’s "Zigeunerweisen". Gibbons argues another parallel between Catherine’s themes of infidelity and death and the film Zigeunerweisen (dir. Seijun Suzuki), “in both plot themes and narrative structure, using concepts of duality, death, to frame a complex and occasionally unintelligible work” (152). The final boss stage is an encounter with Thomas Mutton, revealed to be responsible for the string of recent deaths. The stage is backed by an electronic remix of Polish composer Frédéric Chopin’s 1831 “Revolutionary Étude”. Chopin's anger towards the Russian occupation of Poland in the November uprising (Nercessian 110) mirrors Vincent’s final vengeance against Thomas Mutton and all the demons who imprisoned him in his subconscious. This confrontation is the metaphorical conclusion to Vincent’s character arc, as he finally declares ownership over his physical and emotional life. Afterwards, the player’s ending is revealed, and Trisha leaves them to reflect on the significance—and the sacrifice—of their decision.

Gameplay Video

"Catherine (Game Movie)." YouTube, uploaded by Foxtrod, 16 Oct. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-kAfvxfunCg.

Works Cited

Bizet, Georges. L'Arlésienne Suite No. 2. 1872.

Catherine. Atlus, 2011.

"Catherine (game)." Catherine Wiki, Fandom, https://catherine.fandom.com/wiki/Catherine. Accessed 10 Oct. 2025.

"Catherine (video game)." Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catherine_(video_game). Accessed 10 Oct. 2025.

Cruz, Ronald Allan Lopez. "Mutations and Metamorphoses: Body Horror is Biological Horror." Journal of Popular Film and Television, vol. 40, no. 4, 2012, pp. 160–68.

Dimnet, Ernest. "Ernest Dimnet Quotes." AllGreatQuotes, https://www.allgreatquotes.com/quote-133375. Accessed 10 Oct. 2025.

Fisher, Mark. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books, 2009, pp. 2–9.

Foxtrod. "Catherine (Game Movie)." YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-kAfvxfunCg. Accessed 10 Oct. 2025.

Frow, John. "Character." The Cambridge Companion to Narrative Theory, edited by Matthew Garrett, Cambridge UP, 2018, pp. 105–19.

Gibbons, William. Unlimited Replays: Video Games and Classical Music. Oxford UP, 2018, pp. 3-154.

Hancock, Michael. "Doppelgamers: Video Games and Gothic Choice." American Gothic Culture: An Edinburgh Companion, edited by Joel Faflak and Jason Haslam, Edinburgh UP, 2016, pp. 166–84.

House of the Dead 2. Sega, 1998.

Kirkland, Ewan. "Masculinity in Video Games: The Gendered Gameplay of Silent Hill." Camera Obscura, vol. 24, no. 2, 2009, pp. 161–83.

McKillop, Brendan. "Catherine Videogame Analysis | The Creative Use of Classical Music." YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WSSKo_jjyb0. Accessed 10 Oct. 2025.

Nercessian, A.H. 2002. “Postmodernism and globalization in ethnomusicology: an epistemological problem.” United States: Scarecrow Press, pp. 110.

Phantasmagoria. Sierra On-Line, 1995.

Phantasmagoria: A Puzzle of Flesh. Sierra On-Line, 1996.

Stang, Sarah. "Shrieking, Biting, and Licking: The Monstrous-Feminine and Abject Female Monsters in Video Games." Press Start, vol. 4, no. 2, 2018, pp. 1–34.

The 11th Hour. Trilobyte, 1995.

The 7th Guest. Trilobyte, 1993.

The Typing of the Dead. Sega, 1999.

Zigeunerweisen. Directed by Seijun Suzuki, Cinema Placet, 1980.

AI Disclosure & Appendix

ChatGPT used for acquiring additional scholarly sources.

Prompts used:

- Find all information and metaphors relevant to the video game Catherine Classic.

- Take all of the metaphors and information from the first response and attach them specifically to the sources they come from.

- Sources don't need to speak specifically about Catherine, but they do have to relate to fear, horror, or other at least other themes in Catherine. So more ideas/metaphors can be found that way.

- This paper is specifically about horror video games, and how the conventions/themes in Catherine relates to the broader discussion of the horror genre, and horror video games. Therefore, find sources not just talking about Catherine, but sources also speaking about horror that can be related back to Catherine. Catherine, horror. If speaking on gender, how does that play into horror?

Sources provided (not all were used):

- Bogost, Ian. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. MIT Press, 2007, pp. 29–46.

- Carroll, Noël. The Philosophy of Horror: Or, Paradoxes of the Heart. Routledge, 1990, pp. 28–43.

- Cook, Daniel. “The Nightmare of the Modern Man: Anxiety and Choice in Catherine.” Game Studies, vol. 15, no. 1, 2015, p. 3.

- Creed, Barbara. The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. Routledge, 1993, pp. 27–36.

- Fisher, Mark. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books, 2009, pp. 2–9.

- Fromm, Erich. Escape from Freedom. Farrar & Rinehart, 1941, p. 111.

- Freud, Sigmund. Beyond the Pleasure Principle. Translated by James Strachey, Norton, 1961, p. 23.

- Houe, Nina Patricia, and Joleen Blom. “Bride, Demon or Alien? Undressing Stigma in Catherine: Full Body.” Proceedings of DiGRA 2020, 2020, p. 6.

- Kristeva, Julia. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Columbia UP, 1982, pp. 2–12.

- Nae, Andrei. Immersion, Narrative, and Gender Crisis in Survival Horror Video Games. Routledge, 2022, pp. 63–70.

- Perron, Bernard. The World of Scary Video Games: A Study in Videoludic Horror. Bloomsbury, 2018, pp. 9–35, 93, 118, 131.

- “Fear in Gaming / Virtual Reality Horror Games and Fear in Gaming.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia, 2023.

- “Scary-game physiological study (EEG): Perceived Stress and Clinical Measures.” PMC / NCBI (Aliyari et al.), 2023.