Omori

SPOILER NOTE: While this page contains many spoilers for OMORI, the big reveal is omitted. Like many OMORI fans, I see this game as an art piece that is best experienced without knowing how the story ends. OMORI's story and intended experience relies on this mystery, allowing the ending to have the impact it does. Since OMORI explores heavy topics, it is still recommended to read the trigger warnings before playing (see Introduction to Themes section for content overview).

Background

OMORI is a psychological horror RPG developed and published by OMOCAT in 2020 (Steam). Before OMOCAT was an indie game studio, she was a person with an idea. OMOCAT, the company’s anonymous founder and OMORI’s creator, began fundraising on Kickstarter back in April 2014, two years after completing the OMORI webcomics (Kickstarter).

The game was initially released on Microsoft Windows and macOS via Steam but gained further popularity following its console release on PlayStation, Xbox, and Nintendo Switch in 2022.

Synopsis

The player character’s titular name, Omori1, was derived from the Japanese term for someone who has withdrawn themselves from society: hikikomori (Fukunaga). Omori certainly embodies this term, and the player is tasked with discovering why. However, as the player searches Omori’s colourful world for clues, it becomes clear that something is very wrong.

1When referring to the title, OMORI is capitalized. When referring to Omori the character, sentence case is used.

Introduction to Themes

The themes thoughtfully expressed within OMORI are widely regarded as the game’s greatest strength. Though initially obscured by the cute, colourful environment, the subject matter discussed within OMORI is quite heavy.

Primarily, OMORI is an exploration of trauma and the many ways one might respond to such trauma. Sometimes accompanied by trauma are feelings related to depression, anxiety, self-harm, and suicide; these topics emerge throughout the story as Omori struggles to process a traumatic event. In contrast, themes such as friendship, self-love, and forgiveness are ever-present, facilitating Omori’s escape from the trauma cycle.

Locations

OMORI’s environmental design is deeply ingrained in the overarching story. Aside from Faraway Town, each location represents a common method of trauma avoidance.

White Space

The player is first thrust into White Space, a vast yet minimalistic room. Younis and Fedtke describe the space as a “hollow, risk-free form of escapism” (311). The few items the player can interact with prompt dialogue that only emphasizes the banality of the room.

For Omori, “avoidance of traumatic memories provides momentary solace and safety from anxiety” (Younis and Fedtke 313). Essentially, White Space represents escapism through avoidance, a coping mechanism that prevents Omori from moving forward in the real world.

Headspace

The majority of Omori’s adventures occur in Headspace alongside his friends. Although some danger is present in Headspace, the area is colourful, nostalgic, and brimming with adventure. As Younis and Fedtke write, “Headspace becomes a haven of escapism and safety, allowing Omori a second chance to bask in the comfort that his pre-trauma childhood once provided… Unlike White Space’s avoidant escapism, this type of escapism is characterized by a busy and highly stimulating atmosphere that seeks to distract the individual from any triggers” (318). Unfortunately for Omori, triggers do emerge, often in the form of a dark, looming figure. These haunting interruptions to the nostalgic atmosphere make the environment seem uncanny: “It constantly feels ‘not quite right, familiar but unfamiliar,’ since it is a joyful and comforting space that is sometimes interrupted by horrific entities that slip through the cracks” (Younis and Fedtke 322).

Black Space

Unlocked after exploring Headspace in full, a disorienting and frightening room, called Black Space, is unlocked. In the room, several scattered doors wait to be entered, but none advance the story. Instead, they primarily serve to reinforce “the sense of fear and emotional disarray that arises as a result of triggers” (Younis and Fedtke 322). As the player gets closer to discovering the source of Sunny’s trauma, the “anxiety and confusion [of Black Space] mimic the experience of trauma recovery” (326).

Faraway Town

In the real world, Sunny lives in Faraway Town. Unlike in Headspace, his real friends have been impacted by their grief, and interacting with them reminds Sunny of his trauma. However, even within his own home, there are many upsetting areas that Sunny evades. As a result, he prefers to avoid Faraway Town due to the lack of protection from triggers.

Characters

In OMORI, friends can become enemies, and enemies can become friends. From powerful antagonists to friendly acquaintances, hundreds of characters emerge throughout the story. As a result, this section only covers those most central to the story.

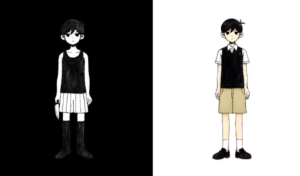

Omori/Sunny

The player will spend most of the game playing as Omori, a quiet boy with a sad expression. As the story develops, however, the player learns that Omori is a coping mechanism for Sunny.

Sunny is the only other player character, and, initially, the player is unsure how the pair is related despite their strong resemblance. After the source of Sunny’s trauma is revealed, we learn that Omori, as well as the world he occupies, are figments of Sunny’s imagination. The fantastical adventures that Omori embarks upon are a colourful distraction from Sunny’s past. The friends he has in this world are memorialized, pre-trauma versions of their true selves. In the real world, Sunny operates as a hikikomori, isolating himself from his friends since their shared tragedy.

The player must choose whether to continue as a hikikomori or rekindle Sunny’s friendships by either opening the door to an old friend or keeping it shut. This early decision determines which of the two routes the game will branch off into. In the Sunny route, which unlocks the good ending, the player will spend a large portion of the game playing as Sunny. In the Omori route, however, the player will primarily play as Omori and will be unable to escape Sunny’s cycle of trauma.

Friends

Omori’s friends (Sunny’s old friends in the real world) include Basil, Aubrey, Kel, and Hero. In Sunny’s imaginary world, his friends never experienced trauma. The world he constructed allows Sunny to spend time with his friends without having to confront the grief that separated them.

In Faraway Town, many of his real friends continue to struggle following their shared trauma. Increasing mental health struggles and low self-esteem have rendered Basil defenseless against bullies. One of those bullies is Aubrey, who perceives that her friends, especially Sunny and Basil, abandoned her when she needed them most. Kel and Hero, however, go out of their way to make sure Sunny and Basil feel safe and included, even when they cannot advocate for themselves.

Mari

Mari is Sunny’s older sister. In Faraway Town, Mari doesn’t tag along for adventures but instead appears in convenient locations, offering the group a picnic. Interacting with Mari’s picnic allows the player to save, view uncompleted quests, or revive the party’s HP.

SOMETHING

In many of Omori’s darkest moments, his only companion is a dark, looming figure called SOMETHING. Omori is petrified by SOMETHING’s frequent presence. Whenever the figure emerges, the brightness dims, and the music gives way to eerie sounds.

Gameplay

The primary objective within Headspace is to find Basil once he disappears. Including finding Basil, most objectives serve the greater purpose of confronting Sunny’s trauma. View gameplay video here.

Mechanics

There are several mandatory and optional side quests to complete throughout the game. An early quest involves solving a hangman puzzle, and collecting lettered keys scattered throughout Headspace is required to advance the story. Each new key provides the player with vague, yet disturbing, context. As Dewanto and Suprajitno write, “the repetition of keypads and their secrets symbolizes the recurring nature of traumatic memories… Each keypad encounter subtly reminds players of Sunny’s trauma through these repetitive, symbolic elements” (294).

Combat

OMORI employs turn-based combat that relies on characters’ emotions, using rock-paper-scissors logic to influence battle outcomes. As Leonardo and Rossi write, “in-game events can alter characters’ emotions, linking narrative progression directly to gameplay (119). For example, we see “Kel throwing a ball at Omori who, failing to catch it, becomes sad and increases his defence” (121). These interactions “provide narrative depth, reflecting the real-world complexities of mental health issues and their impact on individuals’ interactions and behaviours” (119).

Video Games as Art Mediums

Due to the uniquely participatory nature of video games, it was important to OMOCAT that OMORI be a game: “Games do everything that art is supposed to do and beyond. It mixes visuals, writing, music and sound, storytelling, and interaction and puts it all in one package… As creating games becomes easier in the future, I want to get across the idea that game-making is an art medium. I am creating an art piece called OMORI and my medium is a video game” (Kickstarter).

Video games have not always treated mental health depictions with the compassion they deserve. A study from 2019 found that 97% of the games they reviewed “portrayed and perpetuated well-known stereotypes and prejudices associated with mental illness, namely, that those with mental illness (especially psychosis) are violent, scary, insane, abnormal, incapable, unlikely to get well, isolated, and fearful” (Ferrari et al. 8). Since then, more games have embraced the art medium as a means to promote empathy and understanding surrounding mental illness. In another study, Castiglione discovered OMORI to be an alternative, yet “powerful educational tool” that allows players to deal “with complex issues through the playful context of serious games” (2).

Video games place the player in unfamiliar circumstances and require them to make decisions, making it easy, if not necessary, to view the world through someone else’s eyes. Also true of OMORI, a recent study of found that “the game helps generate empathy towards individuals who have undergone similar experiences and marks a step closer towards de-stigmatizing the discussion of matters related to trauma and mental health as a whole” (Younis and Fedtke 333-34). OMORI has repeatedly been studied and praised for its meticulous and insightful depiction of trauma, contributing to the increased acceptance of video games as tools for learning and healing.

Reception

The reviews for OMORI are “Overwhelmingly Positive,” the best possible rating awarded to games listed on Steam. Many reviews praise the game’s story-rich gameplay, and in others, players describe the positive impact OMORI has had on their lives. OMORI’s emotional impact has also been discussed in studies, magazines, and news articles.

A touching personal essay on OMORI was published in The Michigan Daily following the game’s console release. The author details her isolating experience as “a Desi student in a school of white kids,” relating her later growth to Sunny’s triumphs: “lovely, hand-drawn images of family, friends and happiness flash by as the music swells and you feel a release as you reflect on what fueled your fight to feel… your happiness that is so ecstatically sweet when you know how hard you fought for it” (Johri).

On the r/OMORI subreddit, many posts are deeply personal. One post titled “I don't think that any other game, art, movie, or book will elicit my emotions in the way that Omori did” aptly summarizes the community’s relationship to the game (lizardagony). Another post shares a meme with the title, “I finished this game for the first time and now I have a post game depression” (AgentLate6827). In the comments under this post, the triggering nature of OMORI’s content is discussed, with many sharing OP’s sentiment. Although some have described playing OMORI as a retraumatizing experience, others believe the game helped them out of a depression. Therefore, it is important for players to read the preceding trigger warnings and take a break if the content feels too heavy.

The OMORI Effect

Fans of OMORI are adamant that the game is best experienced with no prior knowledge of the story. As a result, it became an internet trend to document a streamer’s demeanor before and after playing the game. In many of these videos, players gleefully comment on the quirky characters, but by the end, their body language has shifted entirely. These streamers are often seen staring at the end screen with an empty expression, as if unsure how to behave following such a heavy conclusion. In one video, overwhelming emotion appears in the form of frustration (Bebe). These “before and after” videos were aptly labelled as “The OMORI Effect.”

AI Disclosure

This assignment was completed without the use of AI tools or technologies.

Works Cited

AgentLate6827. “I finished this game for the first time and now I have a post game depression.” r/OMORI. Reddit, 1 Aug. 2024, https://www.reddit.com/r/OMORI/comments/1eho7tk/i_finished_this_game_for_the_first_time_and_now_i/.

Bebe [@bebeislive]. “I will never be the same.” TikTok, 2025, https://vt.tiktok.com/ZSU9VpGem/.

Castiglione, A. “Playing With Trauma: A Case Study.” Journal of Inclusive Methodology and Technology in Learning and Teaching, vol. 4, no. 1, June 2024, doi:10.32043/jimtlt.v4i1.131.

Codamo, Leonardo, and Ludovica Rossi. “‘Everything is going to be okay’. Analysing emotional landscapes in Interactive Digital Narratives through the exploration of complex psychological themes in Omori.” The Italian Journal of Game Studies, no. 11, 2023, https://www.gamejournal.it/i11-06_codamo-rossi/.

Dewanto, Deanya Parahita Nauraputri, and Setefanus Suprajitno. “Exploring Narrative Structure and Immersion in the Game OMORI: Unpredictability and Trauma as Guiding Principles.” Kata Kita, vol. 12, no. 3, Dec. 2024, 291-298, https://doi.org/10.9744/katakita.12.3.291-298.

Ferrari, Manuel, et al. “Gaming With Stigma: Analysis of Messages About Mental Illnesses in Video Games.” JMIR Ment Health, vol. 5, no. 5, 2019, pp. 1-14, doi:10.2196/12418.

Fukunaga, Julie. “Omori is the RPG of Your Dreams (or Nightmares).” Wired, https://www.wired.com/story/omori-rpg-review/.

Johri, Saarthak. “Empathy for the emotionless: Understanding OMORI.” The Michigain Daily, 14 March 2022, https://www.michigandaily.com/arts/b-side/empathy-for-the-emotionless-understanding-omor/.

Kari-Pekka. “OMORI Gameplay Walkthrough Full Game (no commentary).” YouTube, 28 April 2022, https://youtu.be/LuGJl4UVpxQ?si=lKzEQUnsMiMxj_Cf.

lizardagony. “I don't think that any other game, art, movie, or book will elicit my emotions in the way that Omori did.” r/OMORI. Reddit, 12 Sept. 2022, https://www.reddit.com/r/OMORI/comments/xcv1u0/i_dont_think_that_any_other_game_art_movie_or/.

OMOCAT. “GALLERY” Omori Game, https://www.omori-game.com/en/gallery.

OMOCAT. “OMORI.” Kickstarter, https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/omocat/omori.

OMORI. OMOCAT, 2020. Nintendo Switch game.

“OMORI.” Steam, https://store.steampowered.com/app/1150690/OMORI/.

Younis, Aya, and Jana Fedtke. “‘You’ve Been Living Here For as Long as You Can Remember’: Trauma in OMORI’s Environmental Design.” Games and Culture, vol. 19, no. 3, 2024, pp. 309–36, https://doi.org/10.1177/15554120231162982.